Towards a line of chalk

Chalk Lines Image Exchange: conversations and a search for chalk

Chalk has once again reappeared in my work. But then it never really went away. My childhood walks with both sets of grandparents were on the chalk landscapes of Sussex and Kent. In 2016 I cycled a line of ancient chalk and flint paths for A Line Across England, drawn in by the surface of the ground. From its striking white lines stretching across a landscape to the instantly recognisable white cliffs of the South Coast, it has inspired artists over many years.

Unsurprisingly, I was keen to focus on chalk and limestone when the opportunity arose in a recent image exchange project with Richard Keating, Rachel McDonnell and In David Tidsall. In March 2022, we began to explore the idea of ‘emplacement’ in connection with a Walking the Land project. We regularly exchanged digital images by email, with no explanation attached. With each exchange we took inspiration from our walks and the previous set of images.

Looking for chalk in a limestone landscape

The project gradually shifted from emplacement to chalk and limestone. This led me into a deep-dive of the excellent BGS maps (British Geological Survey) as I set off on local walks looking for chalk in a limestone landscape. This was somewhat of an imaginary quest, given that my local landscape is composed of “early Jurassic marine shales, limestones and sands of the Lias Group” and includes “the Marlstone Bed, which is a limy, sandy ironstone… Clays in the lower levels of the Lias Group have been exposed along the” river valleys and “A hard shelly limestone called Banbury Marble occurs in this part of the Lias.” (Source: Oxfordshire Geology)

It was for me more of a visual quest, searching for the familiar white chalk-like marks and lines on my local limestone, a harder form of chalk, that could, in my imagination, stretch to the landscapes where the others in this group were walking, to further afield in England, through the chalk seabed into Europe and beyond.

The first image that I sent to the group on 5 March 2022 began from a walk thinking about boundaries, borders, edges and inter-linkings, of trees, roots, mycelia and of other networks, of plants and people.

For the second image exchange, I was in Norfolk and walking the area where, in 2016, I began my chalk line across England at the start of the Peddars Way. I revisited the spot and spent time walking the surrounding coastline. I sent an image of the beach as it represented my thoughts about the landing and shifting of elements moved by the wind and sea, a continuously evolving landscape. Carrying images from Richard, Rachel and David with me on my walk, I thought too about the elements blowing in and how our works over the course of this project will interweave and create strata-like layers. I was torn between this image and another of the patterns and lines across the wide expanses of sandy beach walked during strong winds.

As the project progressed, I visited the chalk stream and watercress beds at Ewelme, close to where I had passed by on my journey along the Ridgeway during A Line Across England. England has the highest number of these precious chalk streams. Chalk, as a natural aquifer for clean water, brings together the two elements of earth and water, both often found in my artwork (for example, in Tide, I focused on the water’s edge where sea meets land; Puddle Worlds mapped the meeting of rainwater on the ground). Although potentially a source of clean water, it is however impossible to visit a chalk stream in England without being acutely aware of how they are being destroyed. Campaigns led by Feargal Sharkey and Windrush WASP have gained huge public attention so there is hope for a change in direction despite the resistance of government and water companies.

As described by Tim Smedley whose book, The Last Drop, I am currently reading (Picador, 2023: p144):

“Chalk exists elsewhere in the world, but nowhere is there such a mass of it – from the famous White Cliffs of Dover to the Needles of the Isle of Wight, and hundreds of kilometres of underground aquifer in between – than in south-east England. A softer, whiter form of limestone, chalk is made up of countless billions of tiny marine fossils that settled on the seabed during the Cretaceous period. Water percolates easily through chalk, with organic matter filtered out on the way, leaving crystal-clear, almost immediately drinkable spring water. Chalk streams are nearly entirely fed by these springs, with beds of glittering golden gravel and fish and invertebrates that thrive in the exceptionally clean water. Botanically, they are the most diverse of all England’s rivers.” The estimated 246 chalk streams are described in the draft report as the ‘equivalent to the Great Barrier Reef… a truly special natural heritage and responsibility’. (17)* To suck their source dry, therefore, seems unconscionable.”

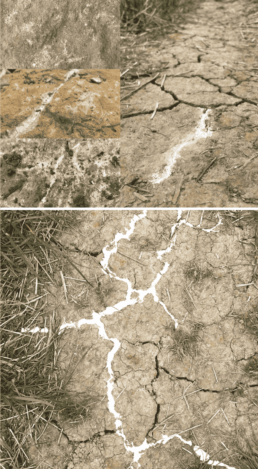

My images (somewhat clumsily) began to incorporate this meeting of earth and water and their lines of interconnection through rivers, streams and sea. On a walk in the countryside not far from home, the path leading ahead through a field was dry cracked mud. The cracks had a river-like, branching quality. I sat down in the middle of the track and began to trace them with chalk. Returning home I mocked up an image on the computer of what they would be like if the cracks were embedded with chalk.

There was something calming about sitting in a field ‘repairing’ the cracks. The process itself was slow and mindful. I was aware of the links to Kintsugi, the Japanese art of repair. I toyed with ideas of how to recreate this on a larger scale in situ, although hit a wall knowing that in England it would inevitably rain at some point during its making and wash away my work long before it was completed. I have various ideas for this as a work and continue to be drawn to the river-like cracks in the surface of paths – maybe at some point it will turn into something more tangible.

I played around with an image that overlaid water and coastlines, in an attempt to capture a sense of flow. The outcome was more successful in my mind than in reality, but these shared images were always intended to be snapshots of thoughts, ideas and works-in-progress. They did not need to be fully resolved. I combined and layered chalk in dried earth lines from a previous image exchange with an image of the surface lines of the River Cherwell and of the seashore on the South Coast of England, where ground and sea meet.

This image also reflected my involvement at the time in Reading Water – Rivers Nile and Thames (a Cop 27 / British Council / Supercluster project). I was thinking about links of chalk and limestone as well as water, lines of geological connection, not just from England into France and other parts of Europe, but also beyond, to Egypt too. Being able to talk to people in Egypt and work together, sharing information about our local rivers, strengthened and brought into sharp focus the many aspects of our interdependent and interconnected lives.

Having made the images as works in progress with no thoughts at the time on their ever becoming a public work, as the Walking the Land spring gathering, Convergence / Divergence approached, Richard, Rachel, David and I met online to discuss how to present our work to date. Each of our images retrospectively became postcards that we each created to exhibit and share at this Walking the Land event.

Towards a Line of Chalk

From my local landscape, as well as other landscapes I have travelled through, I continue this search for chalk and limestone, finding lines that connect stretching increasingly further afield. Looking for chalk and limestone closer to home has been an extension of these works, and has reignited my plan to follow the chalk across the sea to its continuation into other parts of Europe. I wrote about this in an article for Living Maps Review and more recently, about the chalk seabed in one of my letters to Tamsin Grainger for Conversations from a Log.

Although this project has now moved away from the image exchange, as a group we found lots of synchronicities, and no shortage of ideas through the sharing of images and our discussions on Zoom, and will no doubt regroup at some point to share our thoughts and show each other further works we’ve made.

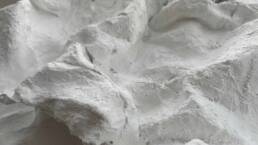

It’s been good to have time to let the ideas settle and potentially make some more substantial pieces. Whilst making a sample demo piece of modroc on paper for a drawing and sculpture workshop that I was teaching earlier this year, it felt and looked like chalk and my mind started to whirr with ideas for how to extend it. A sketch of an idea emerged; one which I might develop further.

From a trip this year to Derbyshire to a recent visit to Croatia, I noticed traces of chalk and limestone. In Croatia, I tried to get a sound recording of the sounds of water dripping through limestone but it wasn’t clear enough to use. The patterns and lines on the limestone rocks of both buildings and coast in Croatia stretched the geological line from my local landscape in England beyond the Channel and North Sea to further afield into Europe. The lines within the limestone drew me in as I traced their marks through sketches and photographs.

These works which continue my engagement with the ground beneath our feet have grown to include seas, oceans, lakes and rivers and is an area of my work that I will continue to develop. Finding geological lines of connection that cross borders and boundaries inspires my work in this area, and chalk, with its tactile nature, and in its many forms, will continue to fascinate me. As Helen Gordon, in her chapter on chalk, in Notes from Deep Time (Profile Books, 2021:pp 113-114) describes:

“As we carried on walking, Farrant and Graham began to discuss differences between chalk formations. To the uninitiated, such differences can seem negligible. Working in chalk is all about getting your eye in, reading the subtlest of clues. The Zig Zag, for example, they described as ‘rather dull, John Major grey’. The Seaford, by contrast, is soft, smooth and bright white and often contains large flints. The Holywell is creamy white, filled with small fossils. The Lewes is white, creamy or yellowish. Chalk rock is very hard, closer to the hard limestones of Cheddar Gorge than the soft, crumbly white stuff that most of us think of as chalk: ‘You wouldn’t want to pick a fight with it.’ Each formation represents a different world, and each of these worlds existed for far, far longer than humans have been on the planet.”

This is part of a series of blog posts presenting my work on recent projects with artists at Walking the Land. Some are completed projects and others are still in-progress. My previous two posts introduced Walking the Land, Abandoned Walks, Roll of Emplacement, and Conversations from a Log. All of these projects were exhibited at Convergence / Divergence, the 2023 spring gathering of Walking the Land. A search for Walking the Land on this website will also bring up previous and future artwork, such as Watermarks (2021) and a Solargraphic project (forthcoming).

If you’d like to find out more about Walking the Land, or become involved, do get in touch, or join the mailing list here. As well as various projects involving different members of the group, there are also regular First Friday Walks (in-person or remote participation) and Last Tuesday Cafés (online).

* Link here for the source of the quote in footnote (17), Chapter 7, p144, of The Last Drop: Solving the World’s Water Crisis by Tim Smedley (Picador, 2023).

Subscribe to be added to my mailing list for occasional updates on exhibitions, events, new artwork and workshops.

I will treat your privacy and personal data with respect . Your details will only be used to send occasional newsletters if you click the link in the confirmation email and you can unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the link at the bottom of the newsletter or sending me an email at ruth@ruthbroadbent.com